Are We There Yet?

Maybe you remember family car trips with the periodic chorus from the backseat “Are we there yet?” The answer was always “Almost,” and somehow you knew that wasn’t true. And yes, you squirmed and asked many more times before the car pulled into the motel, your aunt’s house, a state park, whatever the destination of this trip.

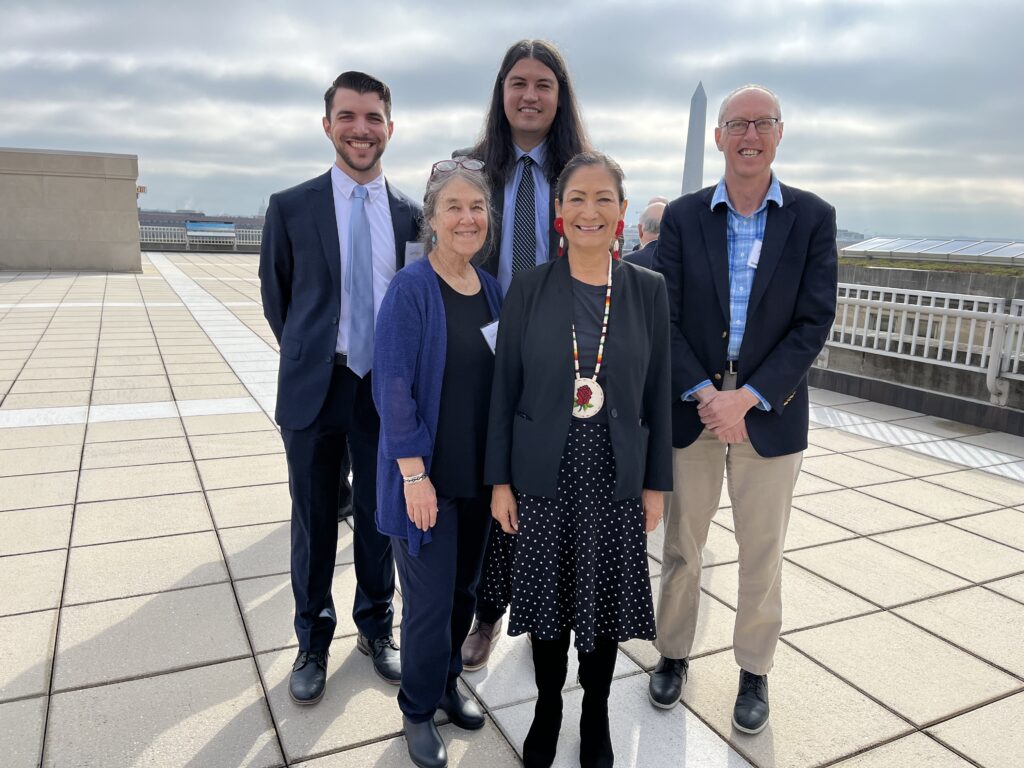

This chorus has been running through my head for the past few weeks as the major project I have been working on draws to a close. On November 1 the final report from the Not Invisible Act Commission was submitted to congress and the Departments of the Interior and Justice. The report addressed the crisis of murdered, missing and trafficked Indigenous people and offered dozens of recommendations to the executive and legislative branches of government.

“So, Lucy,” I tell myself, “the answer is yes, we are there. Your work is done, your contract complete, the final deliverable delivered.” As facilitator I have reached the destination, but the question “are we there yet?” still hangs over me.

The problem is that the report is only one step on a long journey and the real destination is taking action, implementing those recommendations, making significant change that will reduce dramatically the numbers of suffering Indigenous people and families who are impacted by this epidemic of murdered, kidnapped and trafficked Indigenous people. Until that happens I don’t think we’re there yet.

I’ve had this worry before in my decades of mediating and facilitating all kinds of disputes. I’m hired to do a discrete task – hold a listening session, mediate a negotiation, bring adversaries together to draft a plan for moving forward. The outcome may be good, citizens’ voices heard, an agreement reached, relationships built for future work together. But these are just beginnings; they are not the destination. The problem, the need that brought them to the table is still there. Without a monitor, someone responsible for seeing that the agreements become reality, the parties may be left with little or no progress. And in the case of Indigenous and other groups they may simply chalk this up as another broken promise, eroding whatever trust might have been built.

I would like to see the mediator/facilitator be able to take on a follow-through function. With authority to monitor the implementation of the agreement, they could check on progress and help get past obstacles. They could communicate regularly with the parties, reminding them of where they’ve been and where they’re heading, maybe even bring them back together to review, or modify, or celebrate. It’s possible that some participants don’t want to be reminded, are overwhelmed by the newest crisis, or have moved on in another direction. That’s understandable but the work they put in on these processes deserves a careful and caring follow-up. Someone needs to check the road map and ask “Are we there yet?”