Going Home: A Story of Rematriation

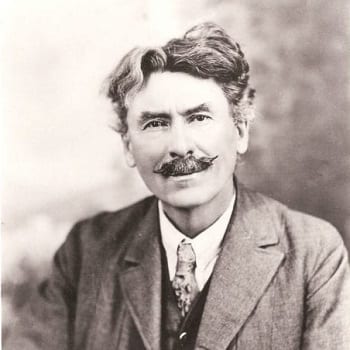

I live in a remarkable community. Seton Village is a few miles outside the Santa Fe city limits and was founded (haphazardly) by Ernest Thompson Seton, conservationist, artist, writer and educator, who moved here from the east coast in the late 1920s. Apparently very charismatic, Seton attracted followers from the east and elsewhere who joined him, first in tipis, later in box cars, and finally in poorly built shelters that eventually became the houses we villagers are in today. The “Chief,” as he called himself, came to the southwest to learn the “Indian way.” He and his wife Julia believed that if we all lived more like Indigenous people, we would be healthier and happier and our communities would be more cohesive and caring. To spread this belief, he developed a program on Native American culture that included folk lore stories, songs and dances, and bits of Native sign language which he had learned from tribal communities in Canada and the northeast.

His interest was sincere and well-intentioned. He hoped to educate and enlighten fellow Whites to the humanity of the “Red Man” (a novel idea at the time) and the superiority of the Native way of life. He hoped to contribute to a shift in the way people lived and how they related to nature and to each other. An early co-founder of the Boy Scouts, he came to see that effort as hierarchical and militaristic, and abandoned it in favor of his Indigenous-based movement which he called the Woodcraft League. The Woodcraft League had minor success in the US, but flourished in Czechoslovakia, Japan and Brazil, where there are avid followers of the Chief to this day. Seton’s life was a story in itself – from trapper to animal advocate, for instance – which is told beautifully in Ernest Thompson Seton: The Life and Legacy of an Artist and Conservationist by David Witt.

Seton died here in 1946, and in 2003 the Academy for the Love of Learning, a nonprofit committed to revitalizing learning for both teachers and students, purchased the property from Seton’s daughter, Dee Barber Seton. The Academy folks have been stellar neighbors to the roughly 20 families that live in Seton Village, opening their facilities to us, sharing in their programs, and respecting our needs. In addition, their Seton Legacy Project stewards and cares for a portion of Seton’s vast collections of books, music, artwork, and Native American textiles, pottery, and other culturally significant items which came with the property.

And here it gets interesting. Aaron Stern, Academy founder, and others on the Academy team, soon realized that Seton’s legacy was complex and that as partial stewards of this legacy they and their board and staff needed to carve a path that honored Seton and his efforts, while also being accountable to the reality and impacts of “cultural misappropriation” on Native people and communities. Difficult questions arose: What if cultural misappropriation was committed in an era before the term and the concept existed? What if the intentions of the cultural appropriator were well-meaning – does that make a difference? What if the impact of the Native appropriation was beneficial, educating people and raising understanding and respect for Native people?

The Academy wanted to be proactive, address the issue and make amends in some way. They hoped the Academy could be a model for other organizations in the same situation. But what to do? Wisely, they asked a group of local Native leaders and scholars for guidance. They generously included me as a representative of Seton Village which sits on the sites of the settlement of Seton and his followers, and of the earlier Indigenous communities back hundreds of years. The group of 12 has met for the past three years, pondering Seton, his legacy and the responsibility of the Academy. The conversations are rambling yet amazingly on point, always with a profound, if not final, conclusion. And in the process, we built our own community which we all treasure and hope can continue indefinitely.

We eventually narrowed our focus to the Seton collection’s “creations” and this word was carefully chosen to describe the great wealth of these collections. The terms “Artifacts” “Objects” “Items” “Crafts” were too cold, too lifeless, too disrespectful. Each creation was created, given life, by an Indigenous artist/craftsperson, and each needed to be treated as an individual being, even in old age when broken, worn or ridden with moth holes. These creations needed to be returned – or “rematriated,” as we said — to their communities of origin, if possible and if desired by those communities.

The Academy took the message seriously and hired two outstanding young Native women to staff the rematriation project. Laura Elliff Cruz and Ash Boydston-Schmidt have developed a process for identifying the tribal origin of over 50 creations in the Seton collection. They reach out to the leadership of those tribes with photos and offer to return the creation. If there is no response, they persist, write, email, phone, seeking out someone at the tribe who might be interested. And if there is a desire to have the creation returned, the Academy offers to bring it to the community, following instructions on how to handle and pack it in an honorable way. Or, if tribal members prefer to come and pick up the creation, the Academy will pay all travel expenses for the trip here and back. To date they have successfully rematriated 26 Indigenous creations. The experience has been thrilling and emotional both for the community recipients and for Laura and Ash.

The Academy for the Love of Learning website has a section on the Rematriation Project where they share their story of returning Native American creations to their cultural homes. They express the hope that the process developed for the return of creations “will inspire other organizations and private collectors to undertake a similar journey of reflection, learning in community, and intentional action.” They are suggesting three practices: “1) the collective questioning of cultural misappropriation; 2) the thoughtful addressing of harm, and 3) a shift in how organizations and institutions view stories — from one lens to many lenses, from narratives of colonization to indigenous lived experience and history.” They also recommend a thoughtful examination of structural racism within the organization, and partnering with local Indigenous communities for guidance and reconciliation.

These insights could have enlightened discussions in a meeting I facilitated between Tribal leaders and National Park Service curatorial staff on the eve of the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). The Act intended to mandate federal agencies, like the Park Service, to seek ways to return Indigenous collections in their possessions. The discussions were heated. Many NPS staff were passionate about preserving culturally significant creations, believing that only they could care for them properly. Did a tribe have climate-controlled facilities? Would they protect the creation from a child’s sticky fingers? Or heaven forbid would they bury it, returning it to the earth, promising certain destruction? Tribal representatives spoke equally passionately about tribal sovereignty and the tribe’s right to handle, preserve or dispose of any item that originated there. There were cultural and religious beliefs and practices that had priority, they said, over non-Indian ideas of preservation. It was a fascinating conversation with no consensus. And today I would guess the same is true. NAGPRA passed in 1990, and there have been successes. But often the efforts fail, due to lack of commitment, lack of a clear process, or perhaps the belief that the item is better cared for by the agency.

I congratulate the Academy for taking the initiative, tackling a very controversial topic, and finding a quiet path through all the noise and conflict. Until now, there has only been direction for the return of creations held by federal agencies. The Academy’s model inspires and offers a clear, practical and respectful process for any organization or individual collector that would like to return one or more creations. Whether it was a gift, a purchase or otherwise, there is a way to rematriate, and the Academy is showing you how. Please see more information and photos of joyful rematriation moments at https://www.aloveoflearning.org/our-work/program/rematriation

Read More